Part of a series of Live Interviews conducted during Global Health Catalyst Cancer Summit at Harvard in Boston

Dr. Oluwole is this awesomely compact and wholesome lady that I met earlier in April at the 2016 Global Health Cancer Catalyst Summit at Harvard, Boston, Massachusetts. Among the pool of presenters at the Summit, Dr. Oluwole shared with infectious optimism on why her Organization – Global Health Innovations & Action Foundation (GHIA-Foundation) – believes that not only can cervical cancer be eliminated in the at-risk-population of 1.3 million Liberian women, but cervical cancer can be eliminated globally within a generation (roughly 25 years), predominantly through the use of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.

As the former founding Executive Director of President and Laura Bush’s Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon partnership, Dr. Doyin Oluwole (who is based in California) is uncomfortable with inaction and believes that a big part of the battle is won when influential parties, like spouses of Heads of States — the First Ladies — are invited to leverage their influence for change.

This space is a DUNIA Magazine exclusive with Dr. Doyin Oluwole.

DUNIA Magazine: Dr. Oluwole, we thank you for this opportunity to talk to us about your presence here at the 2016 Global Health Cancer Catalyst Summit in Harvard, Boston. The main focus in your presentation at this Summit was on coalescing efforts around combating cancer, particularly in so far as mothers and kids are concerned. How important is this focus for an advocate of your caliber?

Dr. Oluwole: Thank you very much for this opportunity to speak with you. My organization is called Global Health Innovations & Action Foundation or GHIA-Foundation. It was established to focus primarily on women: improving health outcomes for women in developing countries, beginning with Sub- Saharan Africa. It leverages an existing platform and layers cervical and breast cancer, screening, treatment on those systems, to prevent siloed programs. And the platform that we have chosen is the maternal health platform.

The reason we did that is because even in developing countries over ninety-five percent (95%) of women will seek health at least once—and now it’s increasing to twice, within the nine months period of pregnancy. It has been a missed opportunity to perform clinical breast examination for breast lumps. It has been a missed opportunity for educating the women on cervical and breast cancer. You can imagine if we were able to provide information to 95% of all the women who get pregnant in developing countries on these two diseases, which kill women in the same age group!

So we want to reduce missed opportunities for care. And we know that we have to do it through partnerships. The continuum of cancer care ranges from advocacy, education, awareness raising to vaccination, secondary prevention, to advanced care, to palliative care; and there’s no single organization that has all the expertise and resources to cover all these areas. And so, this Summit is important because there are experts in each of the components of the continuum of cancer care. And the more people we can get interested in the countries in which we work, and can collaborate with us, whatever their expertise is, the better for us and for the women.

The primary owners of the programs are the countries, but the countries also cannot do this on their own. So they need partners. Here is a good opportunity to meet advocates, to meet experts in all of the fields and network with them and see how we can improve each other’s work.

What has been the reception of this approach in Africa, which I believe is the focus of your organization, especially among practitioners who now have to go an extra mile to do screenings for these pregnant women?

Dr. Oluwole: You know, what we have found, including in my previous job as the Executive Director of Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon at the Bush Institute – working in Botswana, Tanzania and Zambia – is that these health workers are hungry for skills, they are hungry for knowledge. So when you take it to them and they see that it’s the same woman, and they are able to do more for the patients, but on top of that they have the wherewithal to do it – so you are not just training them, you are also equipping them to do it – they are so satisfied. They feel fulfilled.

So we have not received any complaints that “this is too much for us”. No. Everybody’s eyes popped open…like…oh, so we’ve been missing this for our women. And it really does not take much more time because they package it into a comprehensive, essential healthcare service. Plus, it also allows them to test not only for cervical cancer, but also for HIV. Therefore, by the time the woman leaves the clinic she knows the status of her cervix, her breasts, as well as her HIV status. If she comes with a child and the child needs either preventive or curative services, they can refer the child to the nurse that will look after him/her, or at the primary health care center; the same nurse does it. When the patients come back and they smile at the health worker and say “Thank you! Because now I know I have hope that I will not get cervical cancer”, it gives them—the healthcare workers—all the joy.

So, it’s been well accepted by both the policy makers and healthcare workers. The method at the primary health care level is visual inspection with acetic acid, that is household vinegar, followed by cryotherapy. Nurses and midwives can be trained to do it. And then we leave the more complicated procedures for big lesions to doctors. And once you give them the training, the skills and the equipment, they also are delighted to be able to do it. These were procedures they were trained to do, but hitherto they had not had an opportunity to practice. So bringing it to them really gives them job satisfaction. And of course, the policy makers are very receptive to improving outcomes for women who are the bedrock of the nation.

Doctor, you speak with a lot of passion, much more passion than most I know. I have a hypothesis: that most of the people that come to forums such as this either come as passionate professionals or people who have suffered cancer in one form or the other. What ignites the fire in you to carry on with the passion?

Dr. Oluwole: (laughter) I trained as a pediatrician and I was a professor of Pediatrics. But in the course of my work as a clinician, a Professor lecturing and heading the department, I found that a lot of children were dying. I knew what to do. But I could not salvage them. The reason was (that) the women were bringing the children too late. And so I got a grant from the United States Centers for Disease Control to go out there and find out why these children with severe pneumonia were presenting so late. And the result of that survey changed my paradigm completely. It zeroed in on changing the lives of the women.

What were the results?

Dr. Oluwole: I found that the problem resided in the woman. She did not have the decision-making power; she could not recognize danger signs of pneumonia or any disease at that; she had to wait for her husband or mother-in-law to decide on seeking care; she was illiterate or perhaps was dead…. And therefore I shifted focus and I thought: “if I could target the woman, I would be doing good for the child”.

And so WHO (World Health Organization) Regional Office for Africa invited me in 1995 to come and start their integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) program. I did that for a few years and then they promoted me to become the Director for Family and Reproductive Health, which gave me an opening to the mother, the adolescent, the child, the newborn, to nutrition…to gender-based violence. And I can tell you, we made a big difference. And so my passion is not because somebody in my family died of cancer. No. It is not because any member of my family has cancer. No. It is simply because the losses that I see in our countries can be remedied by simple, low-cost interventions, by advocacy, by putting our money where our mouth is.

Women are the pillars of economic development. You’ve heard the World Bank say that investing in the health of women makes economic sense. But it still has not sunken too well into people. And so I go out there and I talk about it and when I have the opportunity to act I do so. In my previous job, I helped to start Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon for President and Mrs. Bush. Before I left we were already in five (5) countries. We had helped to screen, in three (3) of the countries, approximately one hundred and fifty thousand (150,000) women within three and half (3.5) years. We had helped to vaccinate over forty two thousand (42,000) adolescent girls, which meant at least seventy percent (70%) guarantee that those 42,000 girls will not get cervical cancer later in life. It is these types of results that keep the fire burning in me.

…I suppose the vaccine you are talking about is the HPV – Human Papillomavirus Vaccine?

Dr. Oluwole: …Exactly! So why would you not be passionate, when you know that this thing is doable, especially if the resources are available? And that’s why I look out for the key person in the country that will speak to the people, not only speak to the women and the families, but speak to the government. And I have found First Ladies extremely powerful to talk to their husbands—the First Men, to talk to Parliament, to mobilize the women in government, to mobilize international organizations to reallocate resources to support women’s health. I was doing a similar thing that I’m doing for cervical cancer, breast cancer now – I was doing for maternal health when we first started. I was advocating for funding.

At that time we were talking about more than half a million (500,000) women dying in pregnancy. And in Africa, I led my team in WHO to develop a Road Map for Accelerating the Attainment of the Millennium Development Goals Related to Maternal and Newborn Health in Africa. All the forty six (46) countries in the WHO Africa region had a road map, and that’s what they implemented. And today we are talking about two hundred and seventy three thousand (273,000) women dying globally from maternal conditions… See where we came from—500,000 to 273,000—great progress.

I am not saying I am the only one, but there are people like me who are also contributing their quotas. Our collective contributions make a difference. So, it’s a passion to save lives that’s driving me. Because I think we are losing too many useful, productive people in the continent needlessly. A woman need not die in pregnancy. Not one woman should be dying from cervical cancer if we did it right, because it can be prevented.

Mr. Chia, within a generation cervical cancer can be eradicated using HPV vaccination. But are we ready to put our money where our mouth is? That’s why I want to reach to as many people as I can and let them hear it, let me infect them with my passion. And together let’s do what we can. Today, when I remember the one hundred and fifty thousand (150,000) women that three countries screened while I was at Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon, the forty two thousand (42,000) girls that were vaccinated and protected from HPV infection, I smile. I may never know them, but I’m happy that when I had the opportunity I did the little I could do. So, that’s why I’m going all out for let’s declare: “Liberia Cervical Cancer-Free”.

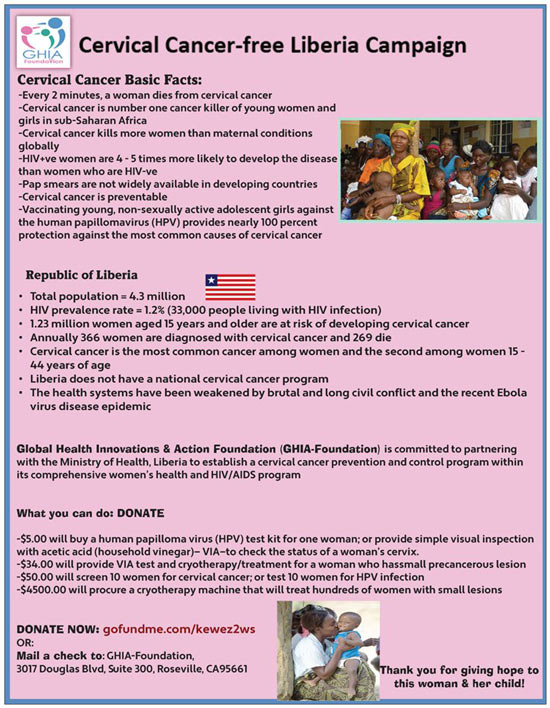

Only one million three hundred thousand (1.3 million) women are at risk of cervical cancer in Liberia. Five dollars ($5.00), given by somebody, would either test a woman for HPV or screen her using visual inspection with acetic acid. Thirty-four dollars ($34.00) donation would screen a woman for cervical pre-cancer and treat her with cryotherapy, if she has a small precancerous lesion. If anybody donated four thousand five hundred dollars ($4,500), we would buy a cryotherapy machine that would treat hundreds of women, who will be given hope that they will not progress to cervical cancer.

So, this is it. And we all need to just see the problem before it becomes another epidemic in our hands. As of 2014, cervical cancer has overtaken maternal deaths as the number one killer of women in the reproductive age group. Globally, two hundred and seventy five thousand (275,000) women now die from cervical cancer every year, compared to 273,000 for maternal deaths (deaths during pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum). And we are seeing an upward trend. We need to curb it before we begin to talk about half a million women dying from cervical cancer.

So, this is the passion. I thank God, my mother gave me the passion because she was a midwife and I saw the way she looked after women. But I thought I could do better than my Mom. So I studied medicine instead of nursing and midwifery.

Thank you so much for your time today.

Dr. Oluwole: I am so grateful for the opportunity. Thank you.

Innocent is on Twitter: @InnoChia

ALSO IN DUNIA MAGAZINE’S CANCER SERIES

– Joyful, Yet Living With A Deadly Form of Cancer – An interview with Liz Omondi

– Transforming Cancer Care in Tanzania (using a replicable model) – Interview with Dr. Twalib Ngoma

– On Cancer Care in Kenya … An interview with Esther Ikiara

– Personalization of problems as a potent antidote in fight against cancer?

Join mailing list for updates and monthly newsletters