Source: China Daily USA; The 'Erhu' Capital Of China

Wuxi’s most famous product is one that bears a stark contrast to its sweet cuisine-a traditional Chinese music instrument that is loved for its sorrowful, melancholic sound. Alywin Chew reports in Wuxi, Jiangsu province.

Such is the city’s reputation for crafting the instruments that it was officially recognized as the “Land of the Erhu in China” by the Chinese Musicians Association in October 2011.

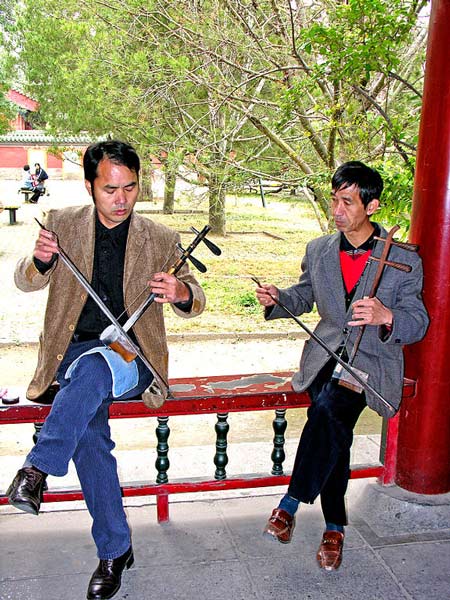

Also known as the Chinese violin in the West, the erhu comprises a long neck with two tuning pegs located at the top and a sound box partially covered with snake skin at the bottom.

Typically made with either redwood, rosewood or black sandalwood, the erhu produces a hauntingly beautiful sound that typically evokes a sense of melancholy among listeners.

Indeed, some of the most famous tunes played on the erhu, such as Moon Reflected in the Second Spring by China’s most famous erhu player, Hua Yanjun, depict this mood.

Hua, more commonly known as A Bing, was born in Wuxi in 1893, and learned how to play a variety of Chinese instruments, including the erhu, when he was a child.

He would then play these instruments as his father, who was a Taoist priest, performed religious rites.

Hua’s life took a downward spiral following his father’s death, and he fell prey to an opium addiction and lost sight in both his eyes after contracting syphilis.

Homeless and penniless, he took to the streets as an itinerant erhu performer, and this was ironically how he eventually came into fame.

But the erhu is more than just a local product-it is the way of life in Wuxi, at least among older folks.

Since 2013, famous erhu players from around the country have been invited to perform at the city’s New Year concerts at the Wuxi Grand Theater as well as on other occasions at the Meicun Erhu Cultural Park.

One can also spot statues of A Bing and hear erhu tunes at various tourist destinations in Wuxi.

But Zhou Sujiang, a music teacher at the Wuxi Arts and Culture Institute, says that while many Chinese are captivated by the heart-wrenching and poignant sounds of the erhu, children and young adults are slow to warm to the instrument.

“There is no other instrument that can produce as melancholic and bittersweet a sound as the erhu. But young people today don’t like such music. They prefer more upbeat and edgy tunes. Interest in erhu classes at the institute is dwindling,” says Zhou.

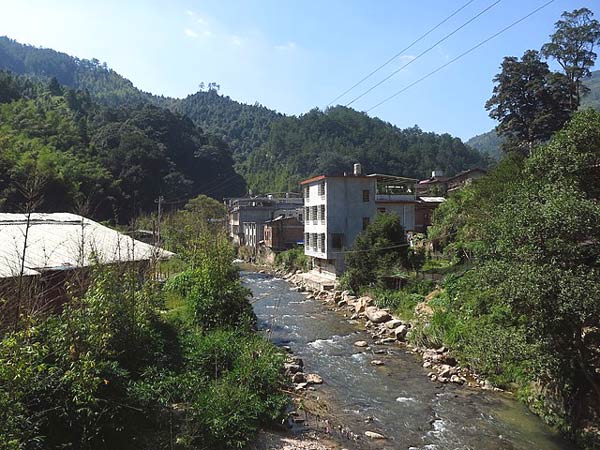

Most erhu makers in Wuxi are based in Meicun, a quiet town northeast of the city center that is said to have more than 3,200 years of history as a vibrant arts-and-culture hub.

According to officials, the town’s links with the erhu date back to 1965 when the first folk-music workshop was founded there.

Chen Shasha, a prominent young erhu player from Meicun, says there are now about 20 erhu makers in the town who produce a combined total of about 50,000 instruments every year, accounting for between 25 and 30 percent of the market share in China.

In December 2010, the town was given the title of “Land of Erhu Craft in Jiangsu Province” by the Jiangsu Folk Literature and Art Association. The next year, Meicun’s erhu-making process was included on Jiangsu province’s list of intangible cultural heritage.

Gu Yue is one of the best-known companies making the instrument in China. And the company-founded by Wan Qixing more than 60 years ago-has a factory in Meicun, which is home to dozens of middle-aged artisans who painstakingly assemble each erhu by hand.

There is no high-tech production line here, just rudimentary tools such as sewing machines, drills, saws and disc sanders.

But the rustic environment is hardly indicative of the quality of the product.

While the company sells basic erhu instruments for a few hundred yuan, it is better known for its exquisite masterpieces that fetch small fortunes.

Bu Guangjun, Wan’s son-in-law, has been working as a supervisor in the factory for the past few decades. He says that one of Gu Yue’s erhu sold for 180,000 yuan ($28,112) at an auction a few years ago.

According to Bu, about 40 percent of the company’s instruments are sold abroad in Asian countries such as Japan, Malaysia and Singapore, while the rest are sold to domestic customers.

Asked why Gu Yue’s erhu are considered to be in a league of their own, Bu cited his father-in-law’s passion and dedication to the craft.

“He’s been doing this for more than 60 years. When you’ve been doing the same thing for so long, you naturally become a master in the craft. He is also a perfectionist and someone who has a keen ear for music,” says the 44-year-old.

“To craft a good erhu, you need more than just technical knowledge-you must also have a feel for the sound.”

This “feel” that Bu mentions also extends to certain processes in the workshop.

For example, the manner in which the snake skin is treated and attached to the sound box is crucial in determining the sound quality, and this step of the crafting process can only be handled by an expert.

“I can determine what type of erhu I can make just by holding a piece of snake skin. It’s all down to the feel. Every piece of snake skin is different. Some are tauter than others. The weather also plays a big role in determining how each piece should be treated. It’s hard to program a machine to identify all these factors,” he says.

“Because of instances such as this, it is almost impossible to completely automate the manufacturing process.”

Gu Yue currently produces about 10,000 instruments per year. Bu notes that production volume peaked in 2012 but has plateaued since. However, he expects domestic demand to pick up again in the coming years.

“The government is now pushing for schools to focus more on arts and culture. The erhu is one of the most famous traditional Chinese musical instruments. So there is bound to be increased interest in it when schools align their curriculums with the government directives,” he says.

—